|

| How can we eliminate rail's carbon emissions? (via Network Rail) |

Previously we've discussed the Reduce, Replace, Repower framework for cleaning up the transport sector, and spoken in general terms about how best to Repower our vehicles - from cars to buses to planes. Today let's take a closer look at how to Repower and decarbonise Victoria's railways.

The TDNS and WRE reports

The most comprehensive work I've seen on this topic is coming out of the UK, with Network Rail's Traction Decarbonisation Network Strategy in 2020 followed by the Railway Industry Association's Why Rail Electrification? report in 2021. The TDNS lays out what a decarbonised Great British railway network would ultimately look like - spoiler alert, mainly electrified - and the WRE report supports their case for widespread electrification.

There are three technologies Network Rail consider mature enough to replace diesel in the short term - Overhead Line Electrification (OLE), battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell (1). The TDNS details which routes should be decarbonised by which method, and why, but not how to get there (eg which lines to do when).

|

| The suitability of different techs for different scenarios (via Network Rail) |

The above graphic shows the first of the broad principles that they've used to make this decision - which of the three options has the technical capacity to do a given task.

The fastest hydrogen trains currently on the market only do up to 140km/h, though the report suggests 160km/h should just be doable soon; battery trains might theoretically reach similar speeds soon, but I'm not aware of any examples that go faster than 100km/h at the moment. So if you want to run a passenger train fast, you have to use OLE. It's much the same for freight; with the sheer amount of power that freight trains need, and the distances that they have to travel, batteries and hydrogen simply don't pack enough punch right now to get the job done. Turns out it's very useful to have a constant supply of electricity over the top of the train that it can plug into!

So why not just put OLE everywhere? Eventually we might, but when prioritising, we need to compare the economics of the different options.

|

| Azuma train under the overhead wires (via Walter Baxter) |

A diesel or hydrogen train is relatively cheap to set up in the first place, but more expensive to run on an ongoing basis. You avoid the expense of building all the poles, wires and substations for electrification (though you do have to set up hydrogen fuelling facilities and so on), but then every train you run is more expensive, because diesel (or hydrogen (2)) is more expensive than electricity. Whereas with OLE, you have larger infrastructure costs upfront, but the trains are much cheaper to run. So the more intensively a line is used, the quicker that upfront investment is paid back, and the more likely OLE stacks up.

|

| Alstom Coradia iLint hydrogen train in Germany (via KlausMiniwolf) |

Remember the 3 Fs - if it's Fast, Frequent or Freight, use OLE. If it's none of those things, maybe look at the other options.

OLE may still make sense for some of these lines - but where it doesn't, the next criterion is distance. Battery trains could do lines up to 100km in length, while hydrogen trains can potentially go much further - although it's worth noting, hydrogen has such poor energy density compared to diesel (even when compressed) that you'd need a tank eight times the size to go the same distance. As mentioned above, speed is another factor, so for short fast(ish) lines you might need to reconsider.

Ultimately Network Rail recommend the vast majority of track, and the vast majority of services, to be electrified - 96% of passenger kilometres and 90% of freight train kilometres would be on OLE.

|

| Vivarail prototype Class 230 battery train (via Spsmiler) |

The Victorian context

We should consider not just what Victoria's network looks like today, but what it could look like in 2035 with a moderately ambitious plan. Whether we go for OLE, batteries or hydrogen, we'll need a completely new fleet - and if we're going to go to the expense of procuring a whole new fleet, it doesn't make much sense to just do a like-for-like replacement with the same 160km/h top speed. We should use the opportunity to upgrade speeds to 200km/h, and get the co-benefit of attracting more passengers. This rules out batteries and hydrogen because they simply can't go that fast, so OLE is the natural choice; maybe with a fleet of pure electric trains, maybe bi-modes, maybe a fleet that includes some of both.

Even if you don't find the case for higher speeds compelling, the main commuter lines already run very frequently, and will only run more frequently in future - meaning the investment in OLE would be paid back relatively quickly in reduced running costs. It just makes sense, whichever way you look at it.

|

| Dual-voltage trains like this Thalys PBKA are common in Europe |

To get the technical details out of the way, we should electrify our regional lines with 25kV AC; this is the world standard for long-distance electrification, it has the power to handle high speeds, and the electrical substations can be placed relatively far apart, reducing costs. Melbourne's suburban network is already electrified to 1500V DC, but dual-voltage trains are very common (in fact the Thalys trains that run from Paris to Amsterdam use these exact two voltages). Trains that need to share tracks with suburban trains (like the Bendigo line) can simply switch between the two voltages as necessary, without the need for expensive retrofits.

|

| Trains run at high speeds and high frequencies on several lines already (via Max Thum) |

The lines that already have higher speeds and higher frequencies - Geelong, Ballarat, Bendigo, Traralgon - should be the first priority to electrify. They have the high frequencies to ensure a short payback time, and they're the best candidates for speed improvements beyond 160km/h.

The Shepparton and Albury lines should be quite close behind. Shepparton needs much better services than it has now, given its size and its proximity to Melbourne; it should be in the same category as Bendigo, and the Regional Rail Revival upgrades are just the first step on that journey. Albury is similarly large, and although it's much further from Melbourne, it has the advantage of being on the way to Sydney - both for passengers and for freight. More on that below.

|

| Long-distance lines like the one to Warrnambool are a bit less certain |

When it comes to the other long-distance lines, some of them are less than 100km from the commuter belt (eg Ararat is 87km from Wendouree) which might mean batteries are appropriate. But Ararat trains currently do 130km/h, and any replacement would need to go at least that fast. Also, some of the turnaround times at Ararat are pretty quick - if a train arrives from Ballarat, would there be enough time to recharge it before it heads back? Maryborough trains only do 100km/h, and run very infrequently, but both of those things should improve to Ararat's level - so again the battery seems like a poor option.

Across all the long-distance lines, either the distances are too long or the speeds are too high for batteries (or they should be). So it seems like all roads lead to hydrogen. (3)

|

| Freight train on the Melbourne-Sydney line (via Marcus Wong) |

The freight side has suffered from chronic under-investment and mismanagement, so which lines actually see enough traffic to justify electrification - and which could see more traffic in the near future - is a slightly tricky question to answer right now. However I think the two interstate mainlines - to Sydney and to Adelaide - should easily see enough traffic to justify electrification. For the rest, though, it's probably important to understand not only the freight volumes but where they intersect with passenger services. This is where we get into the territory of "it should probably happen at some point, but it's not a short-term priority".

Which brings us to...

The rollout

The TDNS doesn't plan the UK rollout, but I think sketching out the Victorian rollout really informs our choices here. The evidence is clear - electrifying our mainlines should definitely happen, and quite soon. There's no technological scenario where we would regret that decision, but if we faffed about for a decade pretending hydrogen would be better, we'd definitely regret that. Canada certainly does. So the highest priority is to electrify our mainlines in rough order of patronage - Geelong, then Ballarat, then Bendigo, then Traralgon, then Seymour/Shepparton, then North East SG, then Western SG.

When we commit to the electrification program, we should definitely also commit to purchasing no new diesel trains. However, at each phase, when electrification is complete, the existing diesel trains can be cascaded throughout the rest of the network - so when Geelong's done, its VLocity units can be used to run Warrnambool trains, or run longer/more frequent Ballarat and Bendigo trains, and so on. This will allow us to replace old locomotive-hauled trains with faster, cleaner VLocity trains, and to run services more frequently, attracting more people out of their cars.

|

| Bi-mode train using diesel engines under unfinished electrification (via Brian Robert Marshall) |

This cascade of rolling stock might undercut the case for bi-mode trains a bit, at least in the short term - anywhere a bi-mode might conceivably be used could probably be run by VLocitys, either as shuttles or by running super-express through the inner parts of the network.

Based on where the tech stands today, hydrogen looks like the answer for the long-distance lines. We could start procuring hydrogen trains quite soon, around the same time we start electrifying the mainlines - and there is certainly a case for moving quickly on this, and retiring diesels early. But realistically, there is a pretty good chance that we'll do what we always do in Victoria, which is saddle the long-distance lines with the hand-me-downs; many of the VLocitys have only rolled off the production line quite recently, so they could keep running around the state for decades if we wanted them to...and I wouldn't be at all surprised if V/Line and the Department did want them to.

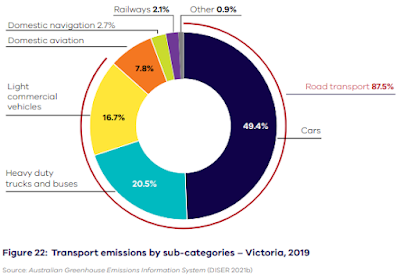

From a carbon perspective, this wouldn't be so terrible. Railways are so efficient that even diesel-powered, our trains represent just 2.1% of our transport emissions (and of course, infrequent long-distance trains represent a smaller slice of that than the frequent commuter-belt services). Given how long it'll take to completely transition the car fleet, diesel trains will remain a low-carbon alternative to driving for most people for a very long time. But it would represent something of a missed opportunity; particularly if hydrogen trains are rolled out as part of a broader package of service improvements (like higher frequencies), the clean green image can help capture the imagination of the travelling public, and be one more way to lure passengers on board.

|

| Rail is a tiny portion of our transport emissions (via DELWP) |

Electrifying all the mainlines (and the associated planning and procurement work) would likely take a good 15 years, so if we did leave the long-distance lines till that's all finished, it's very possible the technological landscape will change by then - or the social landscape, for that matter. Maybe by then batteries will have much higher speeds and further range and we won't need to bother with hydrogen; maybe by then Warrnambool and Colac will be much bigger and we'll be happy to spend the money on poles and wires. Who knows.

So I think the conclusion is this. Hydrogen is probably the winning technology for our long-distance, low frequency lines - at least for now - and ideally we should start rolling that out soon. But the absolutely clear and urgent priority is for us to start planning to electrify our regional mainlines now - they can offer us cleaner, faster trains that can attract more people out of their cars, reduce our emissions, and save operational costs at the same time. Hydrogen cannot do that job, and neither can batteries - and we should not be wasting time pretending otherwise.

1. There is a fourth, Third Rail Electrification (TRE). This has broadly the same characteristics as OLE, but part of the UK's network is already electrified by TRE so they kinda need to electrify adjacent lines by the same method, for compatibility reasons. Victoria doesn't have any TRE, so we don't need to worry about this.

2. Remember the graph from the Repower post? If we use renewable energy to electrolyse water into hydrogen gas, then use a fuel cell to power a vehicle, only 37% of the energy we started with is available for forward motion. With OLE, nearly all of it's available for forward motion. Hydrogen can never be cost-competitive with electricity.

3. One possible exception is the Stony Point line, a quasi-suburban service run by Metro using V/Line diesel trains; passenger demand justifies electrification to Baxter but probably not beyond. But even then, you might need to electrify as far as Hastings for freight trains, at which point it's probably cheaper and easier to just electrify the next 10km or so than to procure a battery train for this line alone.

I think a better strategy would be simply to electrify most lines and increase services to fill the gaps in patronage. Transport is, after all, supply-led rather than demand-led. We should follow the example of a lot of European countries from the 1920s onwards (particularly in the post-war era), but specifically not the UK because they so thoroughly stuffed up their railways between the failed 1955 Modernisation Plan and the 1990s privatisation spree.

ReplyDeleteSwitzerland has had their entire network electrified for decades. Electric trains are able to cope with the long tunnels and steep gradients of such a mountainous country, but the nation also has no indigenous fuel supplies and has to import all fossil fuels. Fuel shortages during the World Wars (and a desire to maintain neutrality and independence) drove them to electrify the remainder. Notably, the Swiss also electrified their freight yards and industrial sidings, and they have recently been trying to improve rail's competitiveness in the short-haul freight sector.

Sweden might be a better example: nearly 85% of the network is electrified, and large parts of the country are very sparsely populated (particularly in the north). The population density of Sweden is actually lower than Victoria, and they've been building new lines to high speed standards to connect towns along the Gulf of Bothnia to supplement and replace the slower 19th century routes that ran inland. We could do the same here: incrementally upgrade our lines to make travel times competitive, run frequent trains so journeys are convenient, and enact policies that encourage a modal shift of freight off roads and onto rail.

A big issue with Australian planning and politics is that we are not ambitious or imaginative enough, and always settle for mediocrity with this false idea that we can't have anything better—Donald Horne's quote about the Lucky Country is more true now that it has ever been. If we set an actual, meaningful target with a long-term plan behind it, the obstacles to a carbon-neutral transport system would not be as insurmountable as they appear.